Today Amsterdam is the “bike capital of the world”. However, this future wasn’t certain.

1950s-1970s

After WW2, Amsterdam mirrored the trend of suburbanization in other cities, especially in the US. Highways, such as the A10 ringroad, were built through and around the city and surrounding neighborhoods. Buildings were demolished, and roads were constructed. Public perception was that cars were the future, and that everyone was going to commute to work from surrounding suburbs.

Kaasjager

H.A.J.G. Kaasjager was a district commander in the Dutch military. During WW2, he denied a request by an SS commander to provide men to be trained as police, and was imprisoned as a prisoner of war for 4 years. In 1946, he was appointed chief of Amsterdam police. Then, on October 20th, 1954, Mayor D’Ailly requested help easing traffic congestion and parking requirements. Kaasjager suggested

- Dredging Canals

- Demolishing historic landmarks

in favor of roads.

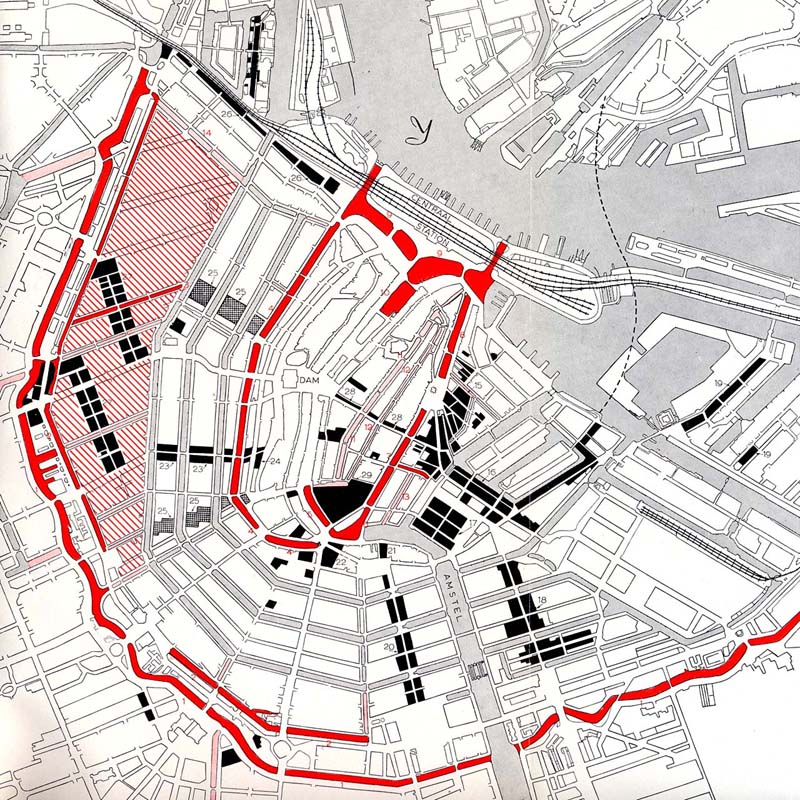

By Geurt Brinkgeve in 1956 pamphlet Alarm in Amsterdam. Displays canals proposed to be filled, and buildings destroyed.

Plan Jokinen

Geef de stad een kans: Een studie uitgevoerd in opdracht van de Stichting Weg, David Jokinen PhD, 1967. Translates to “Give the City a Chance. A Study Comissioned by the Weg Foundation.” The Stichting Weg Foundation was an automobile lobbying group [1] [2]. They commissioned American traffic engineer David Jokinen to design the future of Amsterdam. The plan called for:

- Filling in the Singelgracht canal to create a six-lane highway circling the city center.

- Demolishing working-class neighborhoods like De Pijp and Kinkerbuurt to make way for a major highway (the “Southern Access Road”) and a new central business district.

- Constructing high-rise office towers inspired by La Défense in Paris.

- Building a new central railway station near Weteringcircuit.

- Implementing a monorail system to connect parking garages on the outskirts with the old city center.

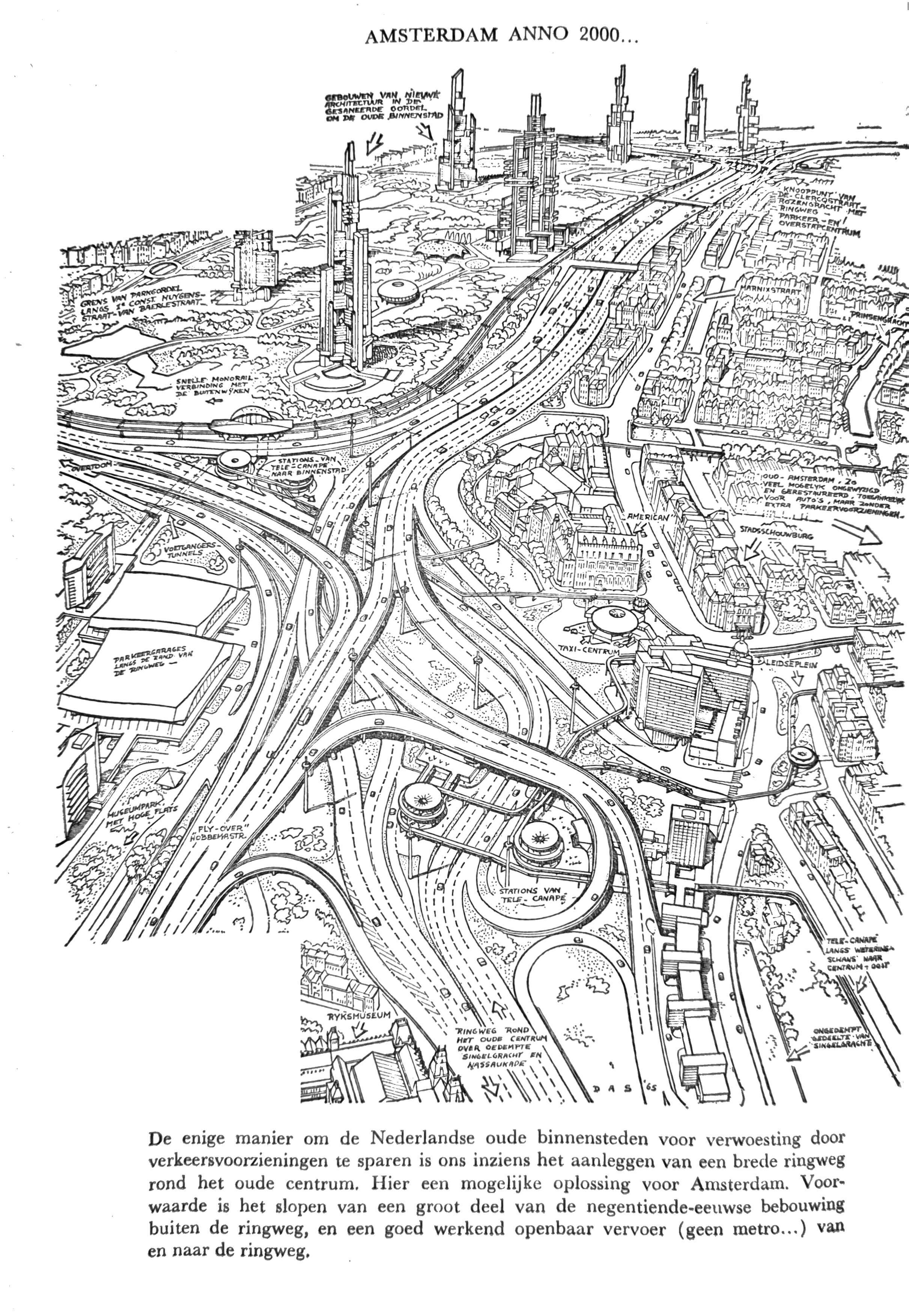

By Robbert and Rudolf Das, published in Op zoek naar leefruimte, 1966

Scan my own. A different scan of this image is widely used without citation, and the image is proported to have been made in support of the plan, but in reality it was made in opposition. Hunting down the source was difficult, but I was able to confirm it by acquiring the book physically. The books WorldCat and Library of Congress pages.

Opposition

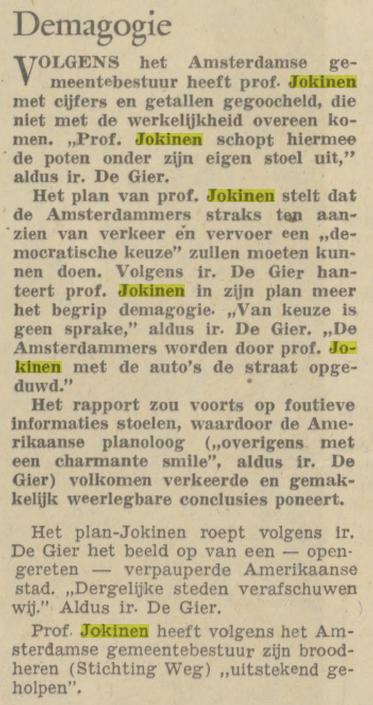

Demagogie. Algemeen Handelsblad. Amsterdam, 12-12-1967. Geraadpleegd op Delpher op 06-03-2025, https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=KBNRC01:000034294:mpeg21:p002

Demagogy ACCORDING to the Amsterdam municipal government, Prof. Jokinen has juggled with figures and numbers that do not correspond to reality. “Prof. Jokinen is kicking the legs out from under his own chair,” according to Ir. De Gier. Prof. Jokinen’s plan states that Amsterdammers will soon have to be able to make a “democratic choice” regarding traffic and transport. According to Ir. De Gier, Prof. Jokinen uses the concept of demagogy more in his plan. “There is no question of choice,” says Ir. De Gier. “Amsterdammers are being pushed onto the streets by Prof. Jokinen with their cars.” The report would also be based on incorrect information, which caused the American planner („with a charming smile, by the way", according to ir. De Gier) to come to completely wrong and easily refutable conclusions. According to ir. De Gier, the Jokinen plan conjures up the image of a — torn open — impoverished American city. “We detest such cities.” According to ir. De Gier. According to the Amsterdam municipal council, Prof. Jokinen has “helped his employers (Stichting Weg) excellently”.

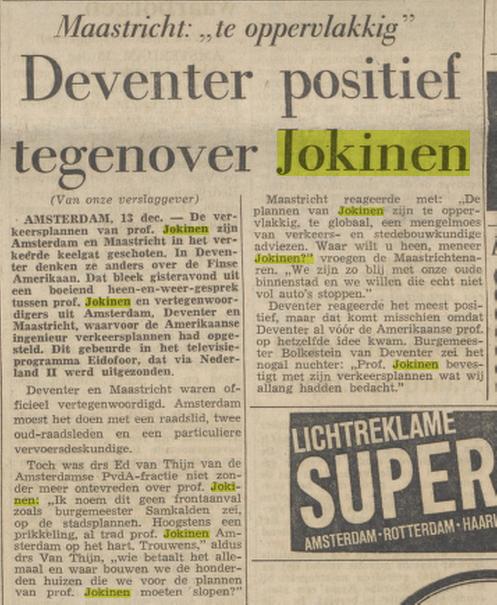

Maastricht: „te oppervlakkig” Deventer positief tegenover Jokinen. De Volkskrant. ’s-Hertogenbosch, 13-12-1967. Geraadpleegd op Delpher op 06-03-2025, https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ABCDDD:010849426:mpeg21:p001

Maastricht: “too superficial” Deventer positive towards Jokinen (From our reporter) AMSTERDAM, 13 dcc. — Prof. Jokinen’s traffic plans have gone down the wrong way with Amsterdam and Maastricht. In Deventer, they think differently about the Finnish American. This became clear last night from a fascinating back-and-forth conversation between Prof. Jokinen and representatives from Amsterdam, Deventer and Maastricht, for whom the American engineer had drawn up traffic plans. This took place in the television program Eidofor, which was broadcast via Nederland II. Deventer and Maastricht were officially represented. Amsterdam had to make do with a council member, two former council members and a private transport expert. Nevertheless, Dr Ed van Thijn of the Amsterdam PvdA faction was not dissatisfied with Prof. Jokinen: “I do not call this a frontal attack, as Mayor Samkalden said, on the city plans. At most a provocation, although Prof. Jokinen did take issue with Amsterdam. Besides,” said Dr Van Thijn, “who is paying for it all and where are we going to build the hundreds of houses that we have to demolish for Prof. Jokinen’s plans?” Maastricht responded with: “Jokinen’s plans are too superficial, too global, a hodgepodge of traffic and urban planning advice. Where do you want to go, Mr Jokinen?” the people of Maastricht asked. “We are so happy with our old city centre and we really do not want to fill it with cars.” Deventer reacted most positively, but that may be because Deventer had already come up with the same idea before the American prof. Mayor Bolkestein of Deventer said it rather soberly: “With his traffic plans, Prof. Jokinen confirms what we had already thought of.”

Dutch people felt that this was being forced on them against their will

Outcome

The plan was rejected with a vote of 22 to 21 in Amsterdam’s city council. Further expansion of car infrastructure was slowed. The “Stop de Kindermoord” campaign grew in popularity.

1970s - 1980s

Due to public pressure, cycling infrastructure began to be prioritized. Pedestrian zones, traffic calming devices, bike lanes and parking, and speed limits began to be introduced. Cycling became normalized as a way to get around.

Late 20th Century and 2000s

Car use starts to rise slowly. 35% of trips under 7.5km, and 48% of all trips, are taken by car in 2005. All others are taken by walking, biking, or with public transportation.

Today

Renewed efforts are being made to reduce car use in the city, with support from residents.

It is clear that the city has developed in a way drastically differently than it would have had its development been centered around cars as was proposed by the Jokinen Plan. Roads are present, but canals haven’t been plugged, and monuments still stand.

My screenshot from here.

My screenshot from here.